Giuseppe Pipino: Geologist-gitologist, ores prospector, mining and metallurgical history scholar.

Short biography

Born in Naples on 6 August 1942, to a Partenopean father and mother from Romagna, he started working as an accountant, after earning the Commercial Accounting Officer Diploma (1961), but in 1963 he moved to Forlì, where he was resident for a short period of time. Following his relatives’ advice, he accepted a seasonal job as a waiter at the International Hotel in Milano Marittima. Although he lacked experience, in a few days he was promoted from comis to chef de rang, thanks to his communicative attitude, to the knowledge (albeit scholastic) of the English and French languages and to his rapid learning of the fundamental German expressions. Later, he joined a group of travelling waiters and he began to work in various parts of Europe for tourist seasons, periodic events and occasional conferences in various towns in Switzerland, Germany, Belgium and France; lastly in 1967 he moved from Marseille to Genoa and there, with the money saved, he bought a restaurant and lived for a few years with Tina, his Genoese partner.

In Genoa he attended the Ligurian Mineralogical Group and, eager to enter University, in 1971 he obtained the scientific High School diploma at Enrico Fermi Lyceum. However, wanting to attend the faculty of geology then considered more important, he moved to Milan, together with his partner, and lived there from 1971 to 1991. Meanwhile he occasionally lived in the countryside near Ovada, between Genoa and Alessandria, the area of his first scientific studies and professional activity.

In 1991 he go to live in the countryside of Rocca Grimalda (AL), where he still lives today. After losing his partner due to an incurable disease, in 1996, he married Irina, a Russian teacher he met in Saint Petersburg at a mining conference. With her he had his only son Pier Paolo.

The wedding with Irina, in 1995, in the church of San Nicolao in San Pietroburgo

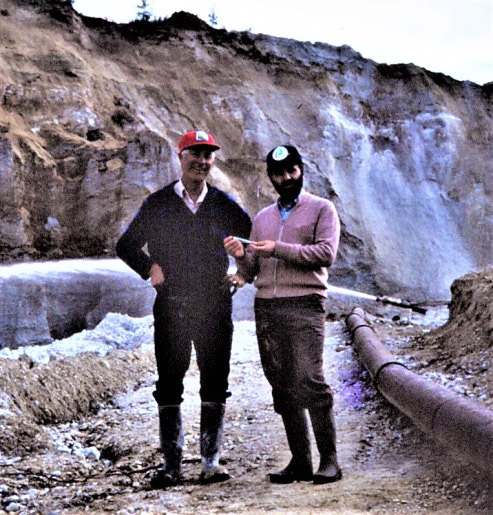

With an operator during a washing of gold mining (ydrauliking) at Dawson City, in 1990

The degree, the scientific contrasts and the professional activity

In Milan, in addition to attending university courses, he immediately joined the Lombard Mineralogical Group and to collaborate with the mineralogical section of the Civic Museum of Natural History. In 1972 he obtained the certificate of attendance, with profit, of the CAI National School of Speleology. In 1975 he obtained a doctoral degree in Geological Sciences with a thesis on "The gold deposits of the Lavagnina Lakes in the Eastern Voltri Group", and a sub-thesis on "Hydrogeological investigations and chemical analyses of sulphur springs of the Voltri Group": the specific studies, carried out at the Institute of Petrography, Mineralogy and Geochemistry of the University of Milan, were part of an extensive multidisciplinary research program on the imposing Apennine ophiolitic complex, started at the Institute of Geology, studies that led to full recognition of its belonging to the Alpine geological domain.

After graduating he briefly collaborated with the Chair of Mineral Depsosits, as a contractor for the National Research Council, a collaboration that led to his first scientific publication (1). Owever, since the preparation of the Thesis, ideological contrasts had begun with the supervisor Prof. Piero Zuffardi, new holder of the chair and head of the faculty, as well as head of the dominant current that saw the syn-sedimentary origin in all the mineral deposits, including the alpine lodes. The detailed study of the gold mineralizations of the Voltri Group and the consultation of Anglo-Saxon texts on similar ores in various parts of the world, convinced him, instead, of their hydrothermal origin.

In 1977 he founded, with some colleagues, the “TEKNOGEO Snc. Geognostic Geological Hydrogeological Investigations” and began to work in the field of applied geology and, at the same time, to collaborate in the mining exploration programs, for nickel, copper and gold, carried out by the American company Phelps Dodge and the Canadian Noranda and Intermogul. The acquired knowledge led to his second scientific publication (2), in which he describes all the Ligurian mineralizations, and deals independently with the genetic problem, opting decisively for their metamorphic and hydrothermal origin. The subsequent participation in an international conference (Cyprus 1979) and the following publication of his speech on the gold in the Ligurian ophiolites (3), put him in contact, as well as with foreign academic circles, with other American and Canadian mining companies: the article is mentioned in countless international studies, as an Italian example of hydrothermal gold mineralization and, more in particular, of deposit formed in ultramafic rocks (listvenite or listwaenite). At the same time, he published an innovative scientific study on the sulphur springs of the Voltri Group, many of which he discovered, with analizing the hydrogen sulphide directly at the source (4).

In 1982 he was included in the international roster of the UN, as an expert in "Geological and Geochemical Exploration” and carried out studies and research on mineral deposits related to the

Arab Emirates ophiolites. In 1984 he set up, in Milan, the new “TEKNOGEO Snc. Geological and Mining Investigations” and undertook mining prospecting in various areas of Italy and abroad, in partnership with major international mining companies. In Italy, in collaboration with Cominco and other associated mining companies, he directed or took part in the exploration of the alluvial gold deposits of the Orba, Elvo and Ticino rivers, of the gold and cupriferous deposits contained in the Ligurian ophiolites, of the base metals’ deposits of the Maritime Alps, the Veneto Alps, Calabria and Sicily, of the cupriferous manifestations and epithermal gold in Southern Tuscany and Lazio. Abroad, he dealt, in particular, with the exploration and exploitation of primary and alluvial gold deposits in Canada, Bolivia, Chile, Mali, Guinea, Sierra Leone and Ghana.

The discovery of epithermal gold in Italy, and the evolution of minerogenic theories

In 1983, following a correspondence with his Italian-American colleague Giancarlo Facca, author of an article on the presence and exploitation of "invisible gold" in some US deposits (5), he began to be interested, occasionally, of the possible presence of epithermal gold mineralizatios in Southern Tuscany, soon reaching the identification of the first evidence, exaggerated by the local press (6) but ignored by the parastatal mining companies directly consulted. Even though they carried out longstanding research in the area, using the advice and expertise of Florentine professors, who followed the "Neptunist” theory supported by Zuffardi, and consequently they did not believe in the possible existence of this type of mineralization. Thanks also to the collaboration of the Italian-Canadian geologist Luca Riccio and the analysis of the samples carried out in Canada, he identified some characteristic deposits in the provinces of Grosseto and Rome, for which in 1986 he asked for some applications on behalf of the newly constituted Cal-Denver Italia Srl: in the prescribed technical reports compiled by him, and taken as scoops by the local press (7), the first scientific observations of this type of mineralization in Italy are contained, in an absolute sense.

The uproar provoked the intervention of the state-owned mining companies which blocked the applications at ministerial level, in spite they had received a favorable opinion from the local mining districts, and the explorations was taken over by them and monopolized. Cal-Denver appealed to the Administrative Regional Tribunal (8), but then had to settle for an economic agreement with Agip Canada, while Teknogeo was offered a substantial consultancy contract by Agip Miniere: this provided for the collaboration of Dr. Pipino in Tuscany and the compilation, for its part, of an inventory of gold clues throughout Italy, starting with Sardinia where, on the basis of his previous indications, the state-owned company was starting collaborative relationships with the regional ones. The positive indications of Dr. Pipino, for Sardinia, were based on mining geology considerations arising from the geological study of areas historically suspected of hydrothermal alteration and the presence of minerals associated with epithermal gold (alum and copper sulphosals) and led to the opening of the Furtei mine and the identification of other deposits in the Sassari area (9). During a conference in Turin, in December 1989, the director of the Regional Company that had publicly attributed to himself the discovery of the Furtei field, was forced to admit: "... he certainly gave a lot to the Italian gold sector, and it seems to me that publicly we can only acknowledge Dr. Pipino, who we can define as the pioneer of gold explorations in Italy "(10).

The investigations and study of the identified epithermal gold mineralizations led, in 1988, to his first scientific publications on the subject referring to Italian deposits, which contain its first characterization and minerogenic hypotheses (11). And this while it was published, by two Florentine researchers a "state of art" resulting from decades of research on the mineralizations of Southern Tuscany, in which the authors completely ignore the possible presence of epithermal gold and speak, again, of "more complex genetic models of the sedimentary-metamorphic type "(12), except trying to attribute to themselves the primogeniture of the studies on the epithermal gold deposits in southern Tuscany and Sardinia, in subsequent publications, in which they do not bring any substantial innovative contribution to the characterization and genesis of the mineral deposits, already stated by

Pipino, and no addition to his list of suspected deposits. In fact, in a popular article published at the end of 1988, completely ignoring the activity and previous publications, one of the two Florentine professors published a generic article on gold which, as regards the "invisible" one, was based on Facca 1982 and, despite the reference in the title ("research for epithermal gold in Italy"), did not provide the slightest specific element and acknowledge that they did not have any concrete data (13): nevertheless, this publication will later be cited as the first on the subject, by the same author and by his collaborators and colleagues. This also because the irritation caused by the publication, in 1989, of another extensive article in which Pipino, in addition to reiterating the data acquired in research throughout Italy, he denounced the backwardness of Italian academics and

their collusion with the para-statal mining companies (14). The "accusations" were then publicly reiterated and proved, by Pipino, in 1992 (15), a few months before the Tangentopoli scandal and the start of the "Mani Pulite" judicial investigation demonstrated that the substantial public resources allocated to the para-statal society for the so-called “basic mining research”, based on “academic” advices, served only to subsidise parties and politicians in a covert way (16).

As for the scientific aspect, the express invitation contained in the 1989 publication, to "... consider the possible migration of low-temperature convoys...without persisting in defending at all costs metallogenic fashion models", had its effect and, with good reason, in the introduction of the volume “Gold, Mines, History” (2003), Pipino can claim “… the contribution given to the so-called evolution of the Italian geological thought”. Not surprisingly, in the new Treccani Italian Dictionary the new lemma "giacimentologo" (gitologist) is associated only with his name.

Mineralogical research, "gold panning" and collection of tangible testimonies

In Milan, in addition to attending university courses, Pipino immediately began to attend the Italian Society of Natural History and the Lombard Mineralogical Group, at the Civic Museum of Natural History, and to participate, with the two associations, in naturalistic and mineralogical excursions in Lombardy and in the neighboring regions. He could thus combine, with the theoretical notions of the University, the direct knowledge of minerals and fossils collected personally or forming part of the museum collections and, especially for minerals, to constitute a discrete personal collection, without becoming a fanatical collector. The study of collected minerals often led to specific publications in the Italian Mineralogical Review, of which he was an editor from 1980 to 1995. At the same time, he actively collaborated with the Regional Museum of Natural Sciences in Turin for the compilation of the "Piedmontese Mineralogical Inventory". Some of his mineralogical publications took on innovative importance: among these, the study of the Voltaggio copper mine and its minerals, some of which, of absolute novelty (sulphate-hydrated carbonates of copper, manganese and aluminum), studied and preserved at the University of Pisa (17), and the description of the "granatites" and contained minerals (18), some of which, rare or unique, such as melanite garnet and perowskite from the upper Orba valley, donated to the Genoa History Natural Museum.

Following the thesis entrusted to him at the University of Milan, his interest was focused on gold and its presence in Italy, a presence which, despite the historical past, at the beginning of his career was ignored, underestimated or completely denied, even academically. Together with some members of the Lombard Mineralogical Group he learned the first gold panning practices in Ticino river, taking advantage of the experience and availability of some old diggers, and soon extended the experience, and the studies, throughout the Po valley, deepening it the historical, cultural and mining aspects. Upon request, in 1981 he held a specific conference at the Polytechnic of Turin on "The gold of the Po Valley", which, published the following year (19), representing the undisputed first point of reference for current historical and scientific knowledge on the topic. Subsequently he will publish specific articles on the gold of the rivers Orba (20), Dora Baltea (21), Elvo (22) and Ticino (23), of the subsoil of Milan (24), and of the Po Valley in general (25), as the result of specific historical-bibliographic research and personal explorations, also carried out using small machinery and pilot plants designed by him. In 1984 he patented instruments designed to recover gold and other heavy

minerals from the sands produced in the quarry plants (26): the bureaucratic obstacles and the lack of the managers collaborative availability prevented the start of serious industrial enterprises, but an intense activity of scattered collection developed, more or less hidden, with a total annual production of a few tens of kilograms of gold.

To convince the skeptics of the real presence of gold, in the late 70s, he began organizing guided tours to the Gorzente gold mines and gathering events in the gold rivers, starting with the Orba. In 1985 he organized the World Goldpanning Championship in Ovada, an event which saw the participation of numerous enthusiasts from all over the world and had enormous prominence in all the media. He continued, for years, to organize championships and gathering events in various parts of Italy, until the next World Championship organized in Vigevano in 1989. This led to the proliferation of enthusiasts, also guided by his publications. At the same time, he had taken to collect all the possible testimonies: in 1981 he constituted a first collection on Orba gold in Casalcermelli (20), in 1987 the Historical Museum of Italian Gold in Predosa (27), in 2020 the specific collection , for the Orba valley, at Cascina Merlanetta in Casal Cermelli (28).

Defined, for these activities, the "prophet of gold", in 2020 he was included in the volume "Gente di Piemonte" by Carlo Patrini (29)..

Historical-bibliographic research and revisions on mining-metallurgical events and techniques

During the preparation of the Thesis, Pipino realized that, since these were ancient mines, useful information could come from the search for unpublished documentation, as well as from an indepth study of the previous bibliography, more or less known. He began frequenting the main Italian archives, starting with those in Genoa, then Turin, Milan, etc., continuing for decades with excellent results, since, thanks to technical knowledge, he could better evaluate historical information and their implications. The materials acquired, in original or in copy, allowed him to set up a specialized library and archive, whose catalogues, published respectively in 2009 and 2014, will be continuously updated on the website www.oromuseo.com. The collect mining documents allowed him, moreover, to publish particular repertories for the Liguria (30), for the Visconti and Sforza Milan States (31), and for the Savoy States (32), as well as for particular aspects such as the “mining regalia” (33) and the medieval collection of gold in the rivers of the Po Valley (34). The publications, all innovative or containing undoubted elements of novelty, will be collected in miscellaneous volumes and, in part, posted on Academia.edu: these, the subject of thousands of views by interested parties, will contribute decisively to increasing specific knowledge and to correct previous errors. In particular, the publication of the repertoire of mining concessions represents a fundamental stage of knowledge for the history of mining law and demonstrates that the mines, whether buried or superficial, have always belonged to the "sovereign" or the "State" and they are outside the ownership of the soil, contrary to what has been argued in centuries-old debates, by many jurists.

The same applies for the gold collection in the rivers in medieval times, for which he clarified, among other things, the question of the evaluation of the metal which, compulsorily sold to the State Mints, as shown in a well-known early medieval document (Honorantie Civitatis Papiae ), it had been the subject of fallacious interpretations in numerous historical and economic publications, which did not take into account the actual and varied content of the metal in the mineral, that is the title of the gold collected (23, 34). As far as Ticino river was concerned, he also pointed out that the historic gold collection could not be considered as a whole, but had to be told by individual sections, called “tratte” (23). As for the Savoy states, in addition to highlighting how wrong were the judgments on the eighteenth-century mining activities and on individual technicians, expressed in numerous Piedmontese publications, he proved that the "Mineralogical School", founded in Turin in 1752, had been the first formally constituted “Mining Academy”, a record erroneously boasted by some European mining centers and completely ignored by Italian scholars (35).

The same criteria for collecting the documentation and evaluating it on the base of his technical knowledge, will also serve to clarify some historical aspects of metallurgy. His study on the amalgamation of gold and silver ores, published by the Polytechnic of Turin, allowed to correct inferences and errors on the subject, and remains fundamental for the knowledge of the real historical and technical application of the procedure (36). His publications on the historic steel industry and on the minerals actually used in the various eras, remain fundamental. He re-evaluated the Genoese low-fire procedure, underestimated by local researchers themselves (37), and prove that, contrary to what is claimed by almost all historians of ancient mines and steel processes, magnetite was not, and could not be used in ancient processes, car its use, in steel, began in the mid-sixteenth century (38). In this regard, it should be noted that in the isolated locality "Le Cave" of Fiorino, in the metropolitan area of Genoa, the Municipality has affixed a bilingual plaque bearing a passage on the mining and steel making activity of the area, in the sixteenth century, taken from a Pipino publications.

Ancient history corrections and archaeological discoveries

The historical research on Italian mines, pushed further and further back in time, will lead him to be interested in classical authors and archaeological remains, as well as to confront (and clash) with the relative interpretations.

In the first year of university, he had attended a course in Palethnology held by Ferrante Rittatore Vonwiller and Francesco Fusco, learning the first rudiments of archeology. He also began to collect the scarce and dispersed passages of classical authors on Italian mine resources, and to continually update their repertoire with ever greater observations drawn from his experiences, so, in many cases, he could correct interpretative and codified inferences concerning the Roman mining law, the institution of the "damnatio ad metalla", the presence and/or exploitation of different ores on the Island of Elba, Arezzo, Ischia, Calabria, Sicily and Sardinia (39), and he reported specific and innovative topics in individual articles about. And, for logical historical connection with the Italian ones, he also analyzed the alleged Roman "aurifodines" of Las Medulas in Spain, declared a World Heritage Site by Unesco, demonstrating that the arguments put forward in the numerous responsible publications are unfounded, and showing many evidence to the contrary (40).

For the Liguria region, the subject of many of his mineralogical and mining history articles, he found himself faced with the problem of recognizing the pre-Roman populations who first became interested in mining, coming to the conclusion that, contrary to what is widespread and codified opinion, the classical sources and the ancient inscriptions do not at all attest that the so-called Ligurians were an ancient and widespread Mediterranean ethnicity, and that "from the point of view of material culture, the only one we are able to grasp and, all in all, the only that interests us, certainly belong to the Celtic world. "(41) The article was republished in the 2000 miscellaneous volume and did not escape the attention of historians and archaeologists, however firm on their preconceived deductions and hypotheses: these were largely abandoned following his subsequent article, overtly exaggerated and provocative (42). At the same time, he addressed the question of the "Possible ancient exploitation of the Murialdo-Pastori mine" by relating it, also with specific chemical analyzes, to a copper pot found nearby (43): the article contains the first well-founded observations on the ancient Western Liguria metallurgy, then continued by officials of the Archaeological Superintendency of Liguria with his collaboration (44).

The greater historical-archaeological interest for the remains of Roman "aurifodine", begun in the mid-80s (45), will lead him to the ever greater definition of those of the Ovada territory (46), of the Dora Baltea river (21), of the Biella territory(47), of the Ticino valley (48), and other minorities he highlighted in the Po drainage basin, as well as in Bohemia (41) and in the Swiss Canton Ticino (49). Their study, and comparison with those existing in other countries, enabled him to trace their general characterization (50) and to publish a specific volume (51). Those of Bessa, in the Biella territory, had previously been the subject of many publications, especially by officials of the old Archaeological Superintendence for Piedmont who arbitrarily confuse them with the Salassi ones, mentioned by

Strabone (52), and contain many inferences and inventions concerning alleged historical, technical and archaeological emergencies (53). In the first organic study of those Roman gold mines (54) he brings the first evidence to support the non-existence of the alleged Vittimuli (or Ictimuli) population who would have cultivated them, an existence even reported in the Italian Encyclopedia; the subsequent historical-bibliographic study, also on ancient Pliny's “Natural History” manuscripts, will lead to the definitive cancellation of that presumed existence (55), despite some nostalgic and preconceived resistance (56). The specific investigation on the ancient toponym had also led him to study, and to solve, the problem of forced identification with others similar or arbitrarily assimilated by the authors, and to conclude that the location of the famous first battle between Scipio and Hannibal, controversial in the hundreds of publications, should not be located “near the Ticino”, but “near Ticino”, ie near the village that had the same name as the river, therefore near today's Pavia.

As for the Salassi gold mines, already in 1987 Pipino had reported some remains to the old Piedmontese Superintendency, warning that they were probably those mentioned by Strabo and mistakenly confused with the Bessa Roman ones. His report and subsequent major specifications, however, collided with interests and with what was stated in publications by some of the officials, and were therefore ignored and boycotted (47). This did not prevent him from continuing his research, discovering other remains, studying and describing them (57). At the same time, starting from 2000, he began to identify the remains of a Limes built by the Romans to defend the mines stolen from the Salassi, also deliberately ignored and boycotted by the same officials for the above stated reasons (58). Even in this case, however, he continued his research, defining the evidence found in more and more detail (59) and publishing, in volume, the complex of archaeological finds discovered downstream of the Ivrea Morainic Amphitheater (60). In his latest publication he highlights how the observation of the archaeological remains facilitates the correct reading of the classical authors and allows to cancel the deductions and inventions of the modern ones, requiring to rewrite the ancient history of the territory between Ivrea and Vercelli(61).

Official recognitions

- Registration, in 1982, in the international roster of the UN, as an expert in "Geological and geochemical exploration".

- Indication of his name, in exclusive form, to mean the term “giacimentologo” in recent editions of the Treccani Italian Vocabulary, and an exclusive reference to his publication for the “xenoblasto” word in the Italian Historical Vocabulary 2019.

- Countless formal letters of recognition and appreciation for his activity, in particular from: USA Geological Survey of Denver (1977), Civic Museum of Natural History of Genoa (1979 and 2021), Falcon Bridge Nickel Mines Lmt. of Toronto (1979), Commission of the European Communities (1982), Italian Society of Natural Sciences of Milan (1985), Banca Popolare Svizzera (1987), Homestake Int. min. Ltd of Vancouver (1987), Agip Miniere of Milan (1989), CNR Ist. Tratt. min. of Rome (1990), School of the State Forestry Corps of Cittaducale (1991), Technische Universitat of Munchen (1995), The Natural History Museum London (1996), Italian Gemological Institute of Milan (1999), University of Genoa (2003), Polytechnic of Turin (2003), Munchen Mineralientage (2008), Suor Orsola Benincasa University of Naples (2009), General Direction for Cultural Heritage of Piedmont (2010), Archaeological Superintendence for Piedmont (2010), University of Bologna (2010), etc.

- Official award, in 1985, of the coat of arms of Ovada, in gold and silver filigree, the highest recognition of the Municipality.

- Insertion of his profile in the book "People of Piedmont" by Carlo Patrini, Ed. "La Biblioteca di Repubblica", Rome 2010, pp. VII (84) and 189-190..

Main pubblications

N.B. The miscellaneous volumes collect some of the articles published previously, grouped by topic; on the Academia.edu website, 67 of them are listed which can be downloaded, and are reported data and indexes of 15 books).

- Pipino G. I giacimenti metalliferi del Piemonte Genovese. Tip. Viscardi, Alessandria 1982.

- Pipino G. Sorgenti e acque minerali di Castelletto d’Orba (Provincia di Alessandria). Comune di Castelletto d’Orba – Amministrazione Provinciale di Alessandria, Tip. Pesce, Ovada 1986.

- Pipino G. La raccolta dell’oro nei fiumi della Pianura Padana. Tip. Novografica, Valenza 1989.

- Pipino G. L’amalgamazione dei minerali auriferi e argentiferi. Una innovazione metallurgica italiana ai tempi dell’Agricola. “Collana Monografie” n. 1, Politecnico di Torino, Museo delle Attrezzature. CELID, Torino 1994.

- Pipino G. Novi Ligure e dintorni. Miscellanea Storica. “Memorie dell’ Accademia Urbense” n. 24, Ovada 1998.

- Pipino G. Le Valli dell’Oro. Miscellanea di geologia, archeologia e storia dell’Ovadese e della bassa Val d’Orba. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2000.

- Pipino G. Le miniere d’oro delle valli Gorzente e Piota. Parco Naturale delle Capanne di Marcarolo – Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Tip. Artistica, Savignano 2001.

- Pipino G. Oro, Miniere, Storia. Miscellanea di giacimentologia e storia mineraria Italiana. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2003.

- Pipino G. Liguria Mineraria. Miscellanea di giacimentologia, mineralogia e storia estrattiva. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2005.

- Pipino G. Documenti minerari degli Stati Sabaudi. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2010.

- Pipino G. L’oro del Biellese e le aurifodine della Bessa. Miscellanea di giacimentologia, archeologia e storia mineraria. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2012.

- Pipino G. Lo sfruttamento dei terrazzi auriferi nella Gallia Cisalpina. Le aurifodine dell’Ovadese, del Canavese-Vercellese, del Biellese, del Ticino e dell’Adda. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2015.

- Pipino G. Oro, Miniere, Storia 2. Miscellanea di giacimentologia, archeologia e storia mineraria. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2016.

- Pipino G. Minerali del ferro e siderurgia antica: alcune precisazioni. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2016.

- Pipino G. Miniere d’oro e limes romano anti-Salassi tra Canavese, Vercellese e Biellese. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2018.

- Pipino G. La “Ruina Montium” di Plinio e la mineria aurifera romana nelle Asturie: osservazioni critiche alla presunta applicazione a Las Medulas e alle aurifodine della Bessa. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2020.

- Pipino G. Miniere d’oro dei Salassi e romanizzazione del Vercellese occidentale e dell’Eporediese: una storia da riscrivere. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2021.

Notes and links

- Pipino G. Le manifestazioni aurifere del Gruppo di Voltri con particolare riguardo ai giacimenti della Val Gorzente. “L’Industria Mineraria” a. XXVII, 1976, pp. 452-468.

- Pipino G. Alcune considerazioni sui giacimenti delle ofioliti liguri. “L’Industria Mineraria” a. XXIX, 1978, pp. 97-107.

- Pipino G. Gold in Ligurian ophiolites (Italy). “Prooceding International Ophiolotes Symposium, Cyprus 1979”, Cipro 1980, pp. 765-773.

- Pipino G. Le sorgenti solfuree del Gruppo di Voltri (Appennino ligure-piemontese). “NATURA” a. LXXII, 1981 n. 3-4, pp. 240-252.

- Facca G. L’oro invisibile. “Le Scienze” n. 165, 1° maggio 1982, pp. 36-49.

- NAZIONE, 19 febbraio 1984: E la Toscana levò un grido: oro. Ce n’è dappertutto secondo un geologo.

- NAZIONE, 25 giugno 1986: Giacimenti d’oro in Maremma. Una società canadese vuol fare ricerche tra Capalbio e Manciano. IL MESSAGGERO, 5 agosto 1986: Giacimenti auriferi a nord di Civitavecchia. Lo sostiene il geologo Giuseppe Pipino.

- NAZIONE, 6 novembre 1987: Per l’oro della Maremma esposto dei canadesi contro l’Agip Miniere.

- Pipino G. L’oro in Sardegna. Da: Inventario eseguito per conto AGIP Miniere, 1987.

- Nuove prospettive per il settore estrattivo…in Sardegna. Interventi e discussioni. “Bollettino dell’Associazione Mineraria Subalpina” a. XXVII n. 3, 1990, pag. 584.

- Pipino G. Manifestazioni aurifere epitermali in Toscana Meridionale. “Bollettino dell’Associazione Mineraria Subalpina” a. XXV, 1988 n. 1, pp. 119-126.

- Tanelli G., Larranzi P. Metallogeny and mineral exploration in Tuscany: state of the art. “Memorie della Società Geologica Italiana” 31(1986), 1989 pp. 299-304.

- Tanelli G. ( 1988) L'Industria aurifera e le ricerche per oro epitermale in Italia. “Energia e Materie Prime” n. 63, sett.-ott. 1988, pp. 89-97.

- Pipino G. Oro invisibile. Indizi e ricerca in Italia. “L’Industria Mineraria” 1989 n. 1, pp. 1-4.

- Pipino G. Il grande imbroglio dell’oro invisibile e della ricerca mineraria in Italia. Relazione e dibattito. “Bollettino dell’ Associazione Mineraria Subalpina ” a. XXIX, 1992 n. 4, pp 446-448.

- Pipino G. La vera storia dell'oro invisibile in Toscana meridionale (e Lazio), “Academia.edu”, 23 ottobre 2014.

- Pipino G. La miniera di rame di Voltaggio (Alessandria). “Rivista Mineralogica Italiana”1980 n. 4, pp. 103-109.

- Pipino G. Granatiti e rodingiti. “Rivista Mineralogica Italiana” 1981 n. 4, pp. 103-116.

- Pipino G. L’oro della val Padana. “Bollettino dell’Associazione Mineraria Subalpina” a. XIX, 1982 n. 1-2, pp. 101-117.

- Pipino G. L'oro dell'Orba e la sua storia nel museo di Casal Cermelli. “Novinostra” 1981 n. 4, pp. 182-185.

- Pipino G. L'oro nel fronte meridionale dell'anfiteatro morenico d'Ivrea e nella bassa pianura vercellese. “ArcheoMedia, L’Archeologia on-line” a. VII n. 17, 16 settembre 2012.

- Pipino G. L’oro del Biellese e le aurifodine della Bessa. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2012.

- Pipino G. L’oro del Ticino e la sua storia. “Bollettino storico per la Provincia di Novara” 2002 n. 1, pp. 90-181.

- Pipino G. Oro a Milano. “Geodes” a. V n. 3, marzo 1983, pp. 82-91. Id. Le alluvioni aurifere del sottosuolo milanese. “Rivista Mineralogica Italiana” 1984 n. 1, pp. 1-8.

- Pipino G. La raccolta dell’oro nei fiumi della Pianura Padana. Tip. Novografica , Valenza 1989.

- Pipino G. Sulla possibilità di recuperare oro ed altri minerali dalle sabbie prodotte in Val Padana. “Quarry and Construction” febbraio 1984, pp. 30-34.

- Pipino G. Il Museo Storico dell'Oro Italiano a Predosa (1987-1994). Otto anni di attività visti attraverso i giornali. Memorie dell’Accademia Urbense n. 15, Ovada 1995.

- L’oro dell’Orba e la sua storia nel museo di “Cascina Merlanetta” a Casal Cermelli.

- Patrini C. Gente di Piemonte. La Biblioteca di Repubblica, Roma 2010.

- Pipino G. Documenti su attività minerarie in Liguria e nel dominio genovese dal Medioevo alla fine del Seicento. “Atti e Memorie della Società Savonese di Storia Patria” n.s. XXXIX, 2003, pp. 39-111

- Pipino G. Documenti minerari viscontei e sforzeschi. “Bollettino storico per la provincia di Novara” vol. 99 (2008) p. 249-318

- Pipino G. Documenti Minerari degli Stati Sabaudi. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2010.

- Pipino G. Notazioni Medievali sulla regalia mineraria. “Academia.edu”, 18 ottobre 2015.

- Pipino G. Documenti medievali sulla raccolta dell'oro in Val Padana,

- Pipino G. Spirito Nicolis di Robilant e l’istituzione della prima Accademia Mineraria in Europa. “PHYSIS”, n. s., XXXVI (1999), 1, pp. 177-213. Id. The first mining high school established in Europe (Turin 1752). “Tradície Banského Školstva vo Svete”, Banská Stiavnica 1999, pp. 247-260.

- Pipino G. L’amalgamazione dei minerali auriferi e argentiferi. Una innovazione metallurgica italiana ai tempi dell’Agricola. “Collana Monografie” n. 1, Politecnico di Torino, Museo delle Attrezzature. CELID, Torino 1994.

- Pipino G. Ferro e Ferriere nell’entroterra di Genova. In “Oro, Miniere, Storia 2”, Ovada 2016, pp. 249-276.

- Pipino G. Minerali del ferro e siderurgia antica: alcune precisazioni. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2016.

- Pipino G. Autori classici e risorse minerarie italiane. “ArcheoMedia. L’Archeologia on-line” a. XVI n. 23, 1° dicembre 2021.

- Pipino G. La “Ruina Montium” di Plinio e la mineria aurifera romana nelle Asturie: osservazioni critiche alla presunta applicazione a Las Medulas e alle aurifodine della Bessa. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2020.

- Pipino G. Liguri o Galli ? Sicuramente Celti! L'età del ferro (e dell'oro) nell'Ovadese e nella bassa Val d'Orba. “URBS” a. X , 1991 n. 1-2, pp. 17-30.

- Pipino G. I Liguri? Mai esistiti! “ArcheoMedia. L’Archeologia on-line”, 30 dicembre 2004.

- Pipino G. Possibile sfruttamento antico della miniera di Murialdo-Pastori

- Del Lucchese A., Delfino D., Pipino G. Metallurgia protostorica in Valle Bormida. In “Archeologia in Liguria”, nuova serie Vol. I, 2004-2005, Genova 2008, pp. 35-57.AA.VV. L’attività metallurgica nel castellaro di Bergeggi. In “ Monte S. Elena (Bergeggi - SV). Un sito ligure d'altura affacciato sul mare”. Scavi 1999-2006” . All’Insegna del Giglio, Firenze 2009, pp. 204-2012.

- Pipino G. La febbre dell’oro degli antichi romani. “Scienza e Vita Nuova”, giugno 1990, pp. 32-37.

- Pipino G. Le aurifodine dell’Ovadese. “ArcheoMedia. L’Archeologia on-line” a. IX n. 3, febbraio 2014.

- Pipino G. L’oro del Biellese e le aurifodine della Bessa. Miscellanea di giacimentologia, archeologia e storia mineraria. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2012.

- Pipino G. Resti di aurifodine sulla sponda piemontese del Ticino in Provincia di Novara. “Bollettino Storico per la Provincia di Novara” a. XCVII, 2006 n. 1, pp. 289-335.

- Pipino G. L’aurifodina di Bombinasco nel Canton Ticino. “ArheoMedia. L’Archeologia on-line” a. VII n.16, giugno 2012.

- Pipino G. Aurifodine e sfruttamento dei terrazzi auriferi. “ArcheoMedia. L’Archeologia on-line” a. VIII n. 22, novembre 2013.

- Pipino G. Lo sfruttamento dei terrazzi auriferi nella Gallia Cisalpina. Le aurifodine dell’Ovadese, del Canavese-Vercellese, del Biellese, del Ticino e dell’Adda. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2015.

- Pipino G. Le miniere d’oro dei Salassi e quelle della Bessa. “L’Universo” a. LXXXV, 2005 n. 5, pp. 629-643.

- PIPINO G. Emergenze archeologiche, vere e presunte, nelle aurifodine della Bessa. “Auditorium. Ricerche, studi, e saggi on line”, 27 luglio 2010.

- Pipino G. L’oro della Bessa. “Notiziario di Mineralogia e Paleontologia” 1998 n. 12, inserto pp.I- XVI.

- PIPINO G. Ictumuli: il villaggio delle miniere d’oro vercellesi ricordato da Strabone e da Plinio. “Bolletino Storico Vercellese” a. 58, 2000 n. 2, pp. 5-27. Id. Le aurifodinae delle Bessa, nel Biellese, e la presunta popolazione dei Vittimuli. “Bollettino Storico Vercellese” a. 62, 2004 n.1, pp. 5-13.

- PIPINO G. Victimula-San Secondo e l’invenzione degli Ictimuli (o Vittimuli). “ArcheoMedia. L’Archeologia on-line” a IX n. 14. 16 luglio 2014.

- Pipino G. L’oro nel fronte meridionale dell’anfiteatro morenico d’Ivrea e nella bassa pianura vercellese. Interesse storico, conseguenze geopolitiche, testimonianze archeologiche. “ArcheoMedia. L’Archeologia on- line”, a. VII n. 17-18, 16 settembre 2012.

- Pipino G. A proposito di “Oro, pane e scrittura”, Salassi, aurifodine di Ictimuli e lapidi funerarie. “Academia.edu”, 6 agosto 2016.Id. Il fantastico cromlech di Cavaglià e altre “eredità Gambari” nel Biellese, e non solo. “ArcheoMedia. L’Archeologia on-line” a. XVII n. 3, 1° febbraio 2022.

- Pipino G. Il Limes romano anti-Salassi dell’Anfiteatro Morenico d’Ivrea. “Academia.edu”, 2 settembre 2017 Id. Le evidenze del limes romano anti-Salassi fra Canaverse e Vercellese. “ArcheoMedia. L’Archeologia on- line” a. XVI n. 13, 1° luglio 2021.

- Pipino G. Miniere d’oro e limes romano anti-Salassi tra Canavese, Vercellese e Biellese. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2018.

- Pipino G. Miniere d’oro dei Salassi e romanizzazione del Vercellese occidentale e dell’Eporediese: una storia da riscrivere. Museo Storico dell’Oro Italiano, Ovada 2021.